Florence, the capital of Italy’s Tuscany region, is renowned for its history, culture, and stunning architecture. This article delves into the vibrant history of Florence, tracing its journey from ancient times to its position as a pivotal city during the Renaissance. Join us as we explore the historical timeline of Florence, highlighting key events, influential figures, and the city’s enduring legacy.

Ancient Beginnings

Etruscan Roots

Florence’s origins can be traced back to the Etruscan civilization, which flourished in central Italy before the rise of Rome. The Etruscans established settlements in the region, leaving behind artifacts and cultural influences that would shape the early development of Florence.

Roman Influence

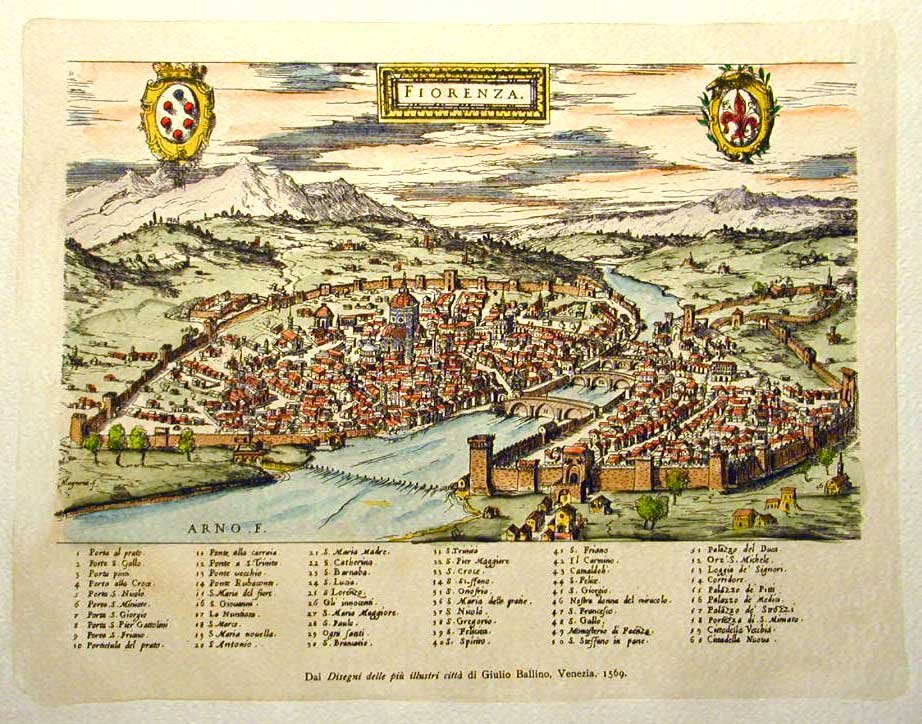

The Romans founded the city of Florentia in 59 BC, strategically located along the Arno River. Florentia became a thriving commercial hub, benefiting from its position on major trade routes. Roman architecture and urban planning laid the foundation for the city’s future growth.

Medieval Florence

Foundation of the City

During the early Middle Ages, Florence underwent significant transformations that set the stage for its future prominence. After the fall of the Roman Empire, the city experienced a period of decline, marked by invasions and political instability. However, by the 9th century, Florence began to revive due to its strategic location along the Arno River, which facilitated trade and communication.

The Carolingian Empire, under Charlemagne, played a crucial role in stabilizing the region. Charlemagne’s reign brought relative peace and economic growth, allowing Florence to start rebuilding its infrastructure and economy. Monasteries and churches were constructed, becoming centers of learning and community life.

The foundation of the city as we recognize it today was solidified in the 11th century. Florence began to develop a more structured urban plan, with the construction of walls to protect against potential invaders. The city’s layout started to take shape, centering around key religious and administrative buildings, which would later include the famous Duomo and Palazzo Vecchio.

Rise of the Merchant Class

By the 11th century, Florence had become a bustling hub of commerce and trade. The rise of the merchant class was instrumental in this transformation. Wealthy families, driven by the lucrative opportunities provided by Florence’s location, began to amass significant economic power. These families were not just traders; they were bankers, wool merchants, and entrepreneurs who played a vital role in the city’s economic and social structure.

The wealth generated by trade allowed these merchants to invest in various sectors, including real estate and art, which laid the groundwork for the cultural blossoming that would define Florence in later centuries. This burgeoning middle class also started to exert political influence, gradually shifting power away from the old feudal nobility.

Florence’s economic success was closely tied to the development of its banking industry. Florentine bankers became renowned across Europe, and the city’s financial institutions laid the groundwork for modern banking practices. The famous Medici Bank, established in the 14th century, became one of the most powerful and respected financial institutions of its time.

Development of Trade Guilds

The establishment of trade guilds in the 12th century marked a significant turning point in Florence’s social and economic history. These guilds, known as “arti,” were associations of artisans and merchants who regulated their respective trades. There were major and minor guilds, with the major ones wielding considerable power and influence.

The major guilds included the Arte della Lana (wool merchants), Arte della Seta (silk weavers), and Arte dei Giudici e Notai (judges and notaries). These guilds set standards for quality, provided training for apprentices, and ensured that their members adhered to ethical business practices. They also played a crucial role in the political life of the city, as guild members often held key government positions.

Guilds contributed to the city’s infrastructure by funding the construction of public buildings, churches, and bridges. For example, the construction of the Ponte Vecchio, Florence’s iconic medieval bridge, was supported by the guilds. This bridge not only facilitated commerce but also became a symbol of the city’s resilience and ingenuity.

Moreover, the guilds’ emphasis on high-quality craftsmanship led to Florence’s reputation as a center for exceptional artisanship. Florentine products, particularly textiles and goldsmithing, were highly sought after across Europe. This reputation for quality helped Florence to establish strong trade connections with other major cities and regions.

Political and Social Structures

Florence’s medieval period was also characterized by the development of its unique political and social structures. The city was initially governed by a consular regime, where consuls elected by the citizens held power. However, as the merchant class grew in influence, they began to demand a greater say in the government.

This led to the establishment of the “Signoria,” a governing body composed of representatives from the major guilds. The Signoria was responsible for making laws, administering justice, and overseeing the city’s defenses. Members of the Signoria were selected through a complex lottery system to prevent the concentration of power and to ensure a fair representation of the various guilds.

The social structure of Florence during this period was stratified, with a clear hierarchy based on wealth and occupation. At the top were the nobility and the wealthy merchant families, followed by the members of the major guilds, and then the minor guilds. The lower classes included artisans, laborers, and peasants, who had limited political power but were essential to the city’s economy.

Religious institutions also played a significant role in Florence’s social and cultural life. The city’s numerous churches and monasteries were not only places of worship but also centers of learning and charity. The influence of the Church extended into politics, with clergy often holding important advisory roles in the government.

Cultural and Intellectual Flourishing

The medieval period in Florence also saw the beginnings of a cultural and intellectual flourishing that would later reach its zenith during the Renaissance. Monastic schools and later, the establishment of the University of Florence in the 14th century, fostered an environment of learning and scholarly pursuit.

Florence became a magnet for scholars, poets, and philosophers. The works of Dante Alighieri, particularly his “Divine Comedy,” reflect the city’s vibrant intellectual life. Dante’s writings not only explored themes of religion and politics but also provided a vivid portrayal of medieval Florence’s society and values.

The city’s architecture from this period also reflects its cultural ambitions. The construction of the Florence Cathedral, with its magnificent dome designed by Filippo Brunelleschi, began in the late medieval period and symbolized Florence’s emerging status as a center of art and innovation. Other significant structures include the Baptistery of San Giovanni and the Palazzo Vecchio, which served as the seat of the city’s government.

In conclusion, medieval Florence was a time of significant growth and transformation. The city’s strategic location, the rise of the merchant class, the establishment of trade guilds, and the development of unique political and social structures laid the groundwork for its later achievements. This period set the stage for Florence’s emergence as a leading center of art, culture, and commerce during the Renaissance.

Florence in the 12th and 13th Centuries

Guelphs and Ghibellines

The 12th and 13th centuries in Florence were marked by intense political strife between two powerful factions: the Guelphs and the Ghibellines. These factions represented broader European conflicts, with the Guelphs supporting the Papacy and the Ghibellines aligning with the Holy Roman Emperor. This rivalry was not merely a political conflict but also a struggle for control over the direction of the city’s future.

The Guelphs and Ghibellines originated from deep-rooted tensions between those who favored a more autonomous church and those who supported imperial authority. This conflict permeated all levels of Florentine society, affecting noble families, merchants, and artisans alike. Major battles between these factions often led to significant violence and upheaval, with control of the city oscillating between them.

In 1216, the conflict intensified with the murder of Buondelmonte de’ Buondelmonti, a nobleman whose marriage dispute sparked further violence. This event polarized the city, with families taking sides and engaging in bloody confrontations. The Guelphs, representing the interests of the Papacy, generally comprised the merchant and banking classes who sought greater independence from imperial control. In contrast, the Ghibellines, supporting the Emperor, included many of the traditional noble families.

One of the most significant battles of this period was the Battle of Montaperti in 1260, where the Ghibellines, supported by the forces of Siena, achieved a decisive victory over the Guelphs. This defeat led to the temporary exile of many prominent Guelph families and Ghibelline dominance in Florence. However, the Guelphs eventually regained control in 1266 after the Battle of Benevento, supported by Charles of Anjou, which marked the beginning of their long-term supremacy in Florentine politics.

Construction of Iconic Structures

Despite the political turmoil, the 12th and 13th centuries were also a period of remarkable architectural and urban development in Florence. The city embarked on an ambitious program of construction, laying the foundations for some of its most iconic structures that would define its skyline and cultural heritage.

Florence Cathedral (Il Duomo)

The construction of the Florence Cathedral, known as Il Duomo, began in 1296 under the design of Arnolfo di Cambio. This grandiose project aimed to reflect Florence’s growing economic power and religious significance. Although the iconic dome, designed by Filippo Brunelleschi, would not be completed until the 15th century, the initial construction of the cathedral symbolized the city’s aspirations and architectural prowess.

Baptistery of San Giovanni

The Baptistery of San Giovanni, one of Florence’s oldest buildings, was given its distinctive Romanesque exterior in the 11th century. By the 12th century, it had become a significant religious and civic landmark. Its bronze doors, particularly the “Gates of Paradise” created by Lorenzo Ghiberti in the 15th century, are considered masterpieces of Renaissance art, though the initial groundwork was laid during this earlier period.

Palazzo Vecchio

The construction of the Palazzo Vecchio began in 1299, intended to serve as the seat of government. Originally known as the Palazzo della Signoria, it housed the city’s governing body, the Signoria, and was a symbol of Florence’s political might. The building’s robust, fortress-like appearance reflected the need for security in a time of frequent conflict.

Ponte Vecchio

The Ponte Vecchio, the oldest bridge in Florence, was first built in Roman times but underwent significant rebuilding in the 12th century. It became a vital commercial hub, with shops lining both sides of the bridge. The bridge’s unique structure and economic importance made it a key feature of medieval Florence.

Economic and Social Developments

The 12th and 13th centuries were also marked by significant economic and social changes. Florence’s strategic location along the Arno River facilitated trade and commerce, attracting merchants from across Europe. The city’s economy was primarily driven by the textile industry, particularly wool, which was processed and traded by numerous artisans and merchants.

Florence’s banking sector also began to flourish during this period. Florentine bankers established a network of branches throughout Europe, facilitating international trade and finance. The establishment of the gold florin in 1252, a widely accepted currency, further solidified Florence’s economic power.

The rise of the merchant class led to the development of a more structured society, with the creation of guilds that regulated various trades. These guilds not only ensured quality and fair practices but also played a significant role in the city’s governance. Members of the major guilds, known as the “Arti Maggiori,” often held key positions in the government, influencing both economic and political policies.

Cultural and Intellectual Flourishing

Florence’s economic prosperity during the 12th and 13th centuries supported a flourishing cultural and intellectual life. The city became a center of learning, attracting scholars and artists. This period laid the groundwork for the later Renaissance, as Florence began to embrace new ideas and artistic expressions.

One of the notable figures of this time was Dante Alighieri, whose works reflect the political and social complexities of Florence. His “Divine Comedy,” although written in the early 14th century, was deeply influenced by the events and culture of the preceding centuries. Dante’s writings provide a vivid portrayal of medieval Florence, capturing its vibrancy and intellectual spirit.

In the realm of architecture and art, Florence saw the construction of numerous churches and public buildings adorned with intricate artworks. The city’s artisans developed a reputation for excellence in various crafts, from textiles to metalwork, which would later become synonymous with the Florentine Renaissance.

The Role of Religion

Religion played a central role in medieval Florence, shaping its culture, politics, and daily life. The construction of grand churches and religious institutions reflected the city’s devout Christian faith and its desire to assert religious influence. Monasteries and convents were not only places of worship but also centers of learning and social welfare, providing education and support to the needy.

The clergy wielded significant influence in Florence’s political affairs, often mediating between conflicting factions and guiding the city’s moral compass. Religious festivals and processions were integral to the social fabric, fostering a sense of community and shared identity among Florentines.

The Birth of the Renaissance

Early Renaissance Beginnings

The early Renaissance, spanning the late 14th to the early 16th centuries, marked a period of profound cultural and intellectual revival in Florence. This era, known as the “Rinascimento,” signified a rebirth of classical learning and a renewed interest in the arts and sciences. Florence was at the epicenter of this transformation, setting the stage for developments that would shape the course of Western civilization.

The seeds of the Renaissance were sown in the late 13th century when Florence began to flourish economically and politically. The city’s wealth, generated primarily through trade and banking, provided the resources necessary to support artistic and intellectual endeavors. Florence’s burgeoning economy allowed wealthy patrons, including the powerful Medici family, to invest in the arts, fostering an environment where creativity and innovation could thrive.

The rediscovery of classical texts played a crucial role in the early Renaissance. Scholars such as Petrarch and Boccaccio sought out ancient manuscripts, studying the works of Greek and Roman philosophers, poets, and scientists. This revival of classical learning, known as humanism, emphasized the value of human experience and rationality. Humanist scholars advocated for education that included a wide range of subjects, including literature, history, philosophy, and the arts.

Influence of the Medici Family

The Medici family, particularly under the leadership of Cosimo de’ Medici, was instrumental in fostering the Renaissance in Florence. Cosimo, who became the de facto ruler of Florence in the early 15th century, was a patron of the arts and an avid collector of classical texts. His support for artists, architects, and scholars helped to create a vibrant cultural scene in the city.

Cosimo’s patronage extended to many of the most renowned artists and thinkers of the time. He financed the construction of significant architectural projects, such as the Basilica of San Lorenzo and the Medici Palace. He also established the Platonic Academy, where scholars gathered to discuss and study the works of Plato and other classical philosophers.

The Medici family’s influence reached its zenith under Lorenzo de’ Medici, known as Lorenzo the Magnificent. Lorenzo’s reign, from 1469 to 1492, is often regarded as the golden age of the Florentine Renaissance. His patronage attracted artists such as Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Sandro Botticelli to Florence, transforming the city into a hub of artistic and intellectual activity.

Artistic Flourishing

The Renaissance saw an unparalleled flourishing of the arts in Florence. Artists began to explore new techniques and styles, breaking away from the rigid conventions of medieval art. The use of perspective, chiaroscuro (the treatment of light and shadow), and anatomical accuracy became hallmarks of Renaissance art, reflecting a more naturalistic and human-centered approach.

Key Artists and Their Works

- Leonardo da Vinci: Leonardo’s contributions to art, science, and engineering epitomize the spirit of the Renaissance. His works, such as the “Annunciation” and “Adoration of the Magi,” showcase his mastery of perspective and detail. Although Leonardo spent much of his later career outside Florence, his formative years in the city were crucial to his development as an artist and thinker.

- Michelangelo Buonarroti: Michelangelo’s early works, including the famous sculpture “David,” were created in Florence. The “David” is celebrated for its detailed anatomy and dynamic composition, representing the pinnacle of Renaissance sculpture. Michelangelo’s work on the Sistine Chapel ceiling, although completed in Rome, was deeply influenced by his Florentine training and sensibilities.

- Sandro Botticelli: Botticelli’s paintings, such as “The Birth of Venus” and “Primavera,” exemplify the idealized beauty and mythological themes characteristic of Renaissance art. His delicate use of line and color, combined with a deep sense of human emotion, made his works stand out during this period.

Architectural Innovations

Florentine architecture also saw significant advancements during the Renaissance. Filippo Brunelleschi’s design of the dome for the Florence Cathedral (Il Duomo) is a masterpiece of engineering and aesthetics. The dome, completed in 1436, was the largest of its kind at the time and remains an iconic symbol of Florence. Brunelleschi’s innovative use of a double-shell structure and herringbone brick pattern set new standards in architectural design.

Other notable architectural projects include the Pazzi Chapel, designed by Brunelleschi, and the Palazzo Rucellai, designed by Leon Battista Alberti. These structures reflected the Renaissance ideals of symmetry, proportion, and harmony, drawing inspiration from classical Roman architecture.

Intellectual Advancements

The Renaissance was not limited to the visual arts; it also encompassed significant intellectual advancements. The development of humanism promoted the study of classical texts and encouraged a critical approach to learning. Florence became a center for the study of the humanities, attracting scholars from across Europe.

The Platonic Academy

The Platonic Academy, founded by Cosimo de’ Medici and led by Marsilio Ficino, played a crucial role in the intellectual life of Renaissance Florence. The Academy was dedicated to the study of Plato’s works and the integration of Platonic philosophy with Christian thought. Ficino’s translations of Plato’s dialogues into Latin made these texts accessible to a broader audience, influencing Renaissance thought and philosophy.

Scientific Inquiry

Florence also saw advancements in scientific inquiry during the Renaissance. Leonardo da Vinci’s notebooks are filled with detailed studies of anatomy, engineering, and natural phenomena. His approach to science, based on observation and empirical evidence, laid the groundwork for the scientific methods that would later be developed.

The contributions of other Florentine scholars, such as Galileo Galilei in the 17th century, further solidified the city’s reputation as a center of scientific innovation. Galileo’s work in physics and astronomy challenged existing paradigms and contributed to the development of modern science.

Political and Social Context

The political and social context of Renaissance Florence played a significant role in shaping its cultural achievements. The city-state was governed by a complex system of republican institutions, with power often concentrated in the hands of influential families like the Medici. Despite periods of political instability and external threats, Florence maintained a relatively stable environment conducive to artistic and intellectual pursuits.

The social structure of Florence was characterized by a growing middle class of merchants, bankers, and artisans, whose wealth and influence supported the city’s cultural activities. Patronage by wealthy individuals and families was crucial in funding artistic projects and fostering a competitive atmosphere that encouraged innovation.

Political Turmoil and Changes

Decline of the Medici

The Medici family, which had dominated Florence for much of the Renaissance, began to face significant challenges by the late 15th century. The family’s influence had grown through strategic marriages, alliances, and their unrivaled patronage of the arts and humanities. However, internal strife and external pressures gradually eroded their power.

Savonarola’s Reign

A pivotal figure during this period of decline was Girolamo Savonarola, a Dominican friar whose fiery sermons and calls for moral and religious reform resonated with a significant portion of the Florentine population. Savonarola vehemently criticized the corruption and excesses of the Medici and the broader church hierarchy. His influence grew to such an extent that, in 1494, following the French invasion of Italy and the subsequent expulsion of Piero de’ Medici (son of Lorenzo the Magnificent), Savonarola effectively became the ruler of Florence.

Savonarola’s regime, often referred to as the “Bonfire of the Vanities,” saw the destruction of secular art, books, and luxury items in an attempt to cleanse the city of its moral corruption. However, his rigid policies and the eventual excommunication by Pope Alexander VI led to his downfall. In 1498, Savonarola was arrested, tried, and executed, marking the end of his theocratic rule.

The Republic of Florence

Following Savonarola’s execution, Florence attempted to restore its republican institutions. The city established a more democratic government, emphasizing broader participation among its citizens, particularly through the Great Council, which was modeled after the Venetian Republic. This period, known as the “Second Republic,” aimed to balance power among Florence’s various social and economic factions.

Machiavelli’s Influence

During this republican phase, Niccolò Machiavelli emerged as a significant political figure. Serving as a diplomat and senior official, Machiavelli’s experiences and observations of political power dynamics greatly influenced his writings. His most famous work, “The Prince,” written after the fall of the Republic, offers pragmatic advice on political leadership and remains a foundational text in political theory. Machiavelli’s ideas were shaped by the turbulent political environment of Florence, reflecting the complexities and challenges of maintaining power and stability.

The Medici Restoration

Despite the efforts to maintain a republic, the Medici family managed to reclaim control in 1512, thanks to the support of the Papal States and the Spanish Crown. The restoration of Medici power marked a significant shift in Florence’s political landscape. The family, now more cautious and strategic, sought to consolidate their rule and avoid the pitfalls that had previously led to their expulsion.

Cosimo I and the Grand Duchy of Tuscany

Cosimo I de’ Medici, who became Duke of Florence in 1537, played a crucial role in transforming Florence’s political structure. In 1569, Pope Pius V granted him the title of Grand Duke of Tuscany, marking the formal establishment of the Grand Duchy. Cosimo I’s reign was characterized by significant administrative, military, and cultural developments that strengthened the Medici’s grip on power.

Cosimo I centralized authority, reducing the influence of traditional republican institutions. He established a powerful standing army and built fortresses to secure the city’s defenses. Additionally, he focused on developing infrastructure, including roads and waterways, to boost trade and economic growth. Cosimo I’s patronage of the arts continued the Medici legacy, supporting artists such as Giorgio Vasari, who documented the lives and works of Renaissance artists in “The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects.”

Political Reforms and Centralization

Under the Medici Grand Dukes, Florence underwent significant political and administrative reforms. The centralization of power in the hands of the Grand Duke allowed for more efficient governance but also reduced the political freedoms previously enjoyed by the city’s citizens. The traditional republican structures, such as the Signoria and the Gonfaloniere, were gradually sidelined or transformed into ceremonial roles.

The Medici rulers established a bureaucratic system that enabled better control over the various territories of the Grand Duchy. This system included the appointment of loyal officials and the implementation of policies aimed at stabilizing and enhancing the economic prosperity of the region. The Medici also pursued diplomatic marriages and alliances, securing their position within the complex web of Italian and European politics.

Economic and Cultural Flourishing

Despite the political centralization, Florence continued to thrive economically and culturally under the Medici Grand Dukes. The city maintained its status as a center of banking, trade, and manufacturing. The wool and silk industries, in particular, remained vital to Florence’s economy, supported by the Medici’s investment in technological innovations and market expansion.

Culturally, Florence experienced a second wave of Renaissance splendor. The Medici continued to patronize artists, architects, and scholars, fostering an environment of intellectual and artistic creativity. The construction of the Uffizi Gallery, initially intended as government offices, became one of the world’s most renowned art museums, housing masterpieces collected by the Medici.

Challenges and Resilience

The Medici Grand Dukes faced numerous challenges, including external threats from rival states and internal dissent. The Thirty Years’ War (1618-1648) and other European conflicts posed significant risks to Florence’s stability and economic health. However, the Medici’s diplomatic skills and strategic alliances often mitigated these threats.

Internally, the centralized Medici rule occasionally sparked resistance from factions within Florence who longed for the republican ideals of the past. However, the Medici’s ability to adapt and reform, coupled with their continued patronage of the arts and sciences, helped maintain their authority and the city’s prosperity.

Florence in the 16th and 17th Centuries

Grand Duchy of Tuscany

The 16th century was a transformative period for Florence as it transitioned from a republic to the capital of the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. This change was solidified in 1569 when Pope Pius V officially recognized Cosimo I de’ Medici as the Grand Duke of Tuscany. This elevation marked the beginning of a new era characterized by centralized power and significant political and cultural developments.

Cosimo I’s Reign

Cosimo I de’ Medici’s reign (1537-1574) was pivotal in shaping the Grand Duchy of Tuscany. He centralized the administration, bringing various independent territories under Florentine control. Cosimo I was an astute ruler who strengthened the state’s military capabilities by building a network of fortresses and a strong navy, ensuring the duchy’s security against external threats.

Cosimo’s domestic policies focused on economic development and infrastructure. He improved the road network, which facilitated trade and communication within the duchy, and invested in the agricultural sector, promoting innovations that increased productivity. His support for commerce and industry, particularly the wool and silk trades, continued to bolster Florence’s economy.

Cultural and Scientific Advancements

The 16th and 17th centuries were also periods of remarkable cultural and scientific advancements in Florence. The Medici’s patronage extended beyond the arts to include sciences and humanities, fostering an environment of intellectual growth and innovation.

The Uffizi Gallery

One of Cosimo I’s most enduring legacies is the Uffizi Gallery. Originally designed by Giorgio Vasari as government offices (uffizi means “offices” in Italian), it soon became a repository for the Medici family’s extensive art collection. The gallery, which officially opened to the public in 1765, houses masterpieces by artists such as Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, and Botticelli. Today, it remains one of the most significant art museums in the world.

Galileo Galilei and Scientific Inquiry

The Medici’s patronage of science is exemplified by their support of Galileo Galilei, one of the most influential scientists in history. Galileo, who was a tutor to Cosimo II de’ Medici, conducted groundbreaking work in astronomy, physics, and mathematics. His improvements to the telescope and subsequent astronomical observations challenged the prevailing geocentric view of the universe, laying the groundwork for modern science.

Galileo’s relationship with the Medici family provided him with the protection and resources needed to pursue his research. Despite facing opposition from the Catholic Church, Galileo’s work flourished in Florence, contributing significantly to the Scientific Revolution.

Architectural and Artistic Achievements

Florence continued to be a center of architectural and artistic innovation during the 16th and 17th centuries. The Medici commissioned numerous building projects that enhanced the city’s grandeur and reflected their power and influence.

Pitti Palace and Boboli Gardens

The expansion of the Pitti Palace, which became the primary residence of the Medici family, is a notable example of their architectural patronage. The palace, originally built in the mid-15th century, was significantly enlarged and enhanced during Cosimo I’s reign. Adjacent to the palace, the Boboli Gardens were created, serving as an elaborate example of Renaissance landscaping. The gardens, with their sculptures, fountains, and grottos, became a model for other European courts.

The Laurentian Library

Commissioned by Cosimo I and designed by Michelangelo, the Laurentian Library is another testament to the Medici’s commitment to cultural patronage. The library, located within the Basilica of San Lorenzo, was intended to house the Medici’s vast collection of manuscripts and books. Michelangelo’s innovative architectural design, characterized by its use of space and light, made the library a significant cultural landmark.

Economic and Social Developments

The Grand Duchy period saw continued economic growth, driven by the Medici’s policies and Florence’s strategic position in European trade networks. The city maintained its dominance in the banking sector, with Florentine banks financing trade and exploration ventures across Europe and the Mediterranean.

Wool and Silk Trade

Florence’s traditional industries, particularly the wool and silk trades, continued to thrive. The city was renowned for the quality of its textiles, which were highly sought after in markets from England to the Ottoman Empire. The Medici’s investments in these industries included the establishment of workshops and training programs to ensure the continuation of high-quality craftsmanship.

Political Stability and Governance

The centralization of power under the Medici Grand Dukes brought relative political stability to Florence. The Medici rulers maintained tight control over the government, reducing the influence of the traditional republican institutions. This period of centralized authority allowed for consistent policy implementation and long-term planning, which contributed to economic and cultural prosperity.

Francesco I and Ferdinando I

After Cosimo I, his son Francesco I de’ Medici (1574-1587) continued the policies of centralization and cultural patronage. Francesco I was known for his interest in alchemy and the natural sciences, founding the Medici Theater of Art and Natural Sciences, which later became the Accademia del Cimento. His reign, however, was relatively short and marked by personal scandals and political intrigue.

Francesco’s brother, Ferdinando I de’ Medici (1587-1609), succeeded him and focused on stabilizing the government and strengthening the duchy’s economic position. Ferdinando I’s reign saw the completion of several significant architectural projects and continued support for the arts and sciences. He also sought to enhance Florence’s international standing through diplomatic marriages and alliances.

Religious Influence and the Counter-Reformation

The Counter-Reformation, a period of Catholic revival initiated in response to the Protestant Reformation, had a significant impact on Florence during the 16th and 17th centuries. The Medici, who were staunch supporters of the Catholic Church, implemented measures to reinforce Catholic doctrine and practices.

The Council of Trent

The Council of Trent (1545-1563) played a crucial role in the Counter-Reformation, addressing issues of church reform and doctrine. Florence, under Medici rule, adhered to the council’s decrees, which included the promotion of religious art and architecture that reflected the ideals of the Catholic Reformation. This led to the construction and renovation of numerous churches and religious buildings, reinforcing the city’s spiritual and cultural identity.

Social Dynamics and Daily Life

The social dynamics of Florence in the 16th and 17th centuries were influenced by the rigid class structure, with the Medici and other noble families at the top, followed by wealthy merchants, artisans, and the working class. The Medici’s patronage extended beyond the elite, as they also supported public works and charitable institutions that benefited the broader population.

Public Works and Charitable Institutions

The Medici invested in public works, such as the construction of hospitals, orphanages, and almshouses, to improve the living conditions of the less fortunate. The Ospedale degli Innocenti, an orphanage designed by Filippo Brunelleschi in the early 15th century, continued to receive Medici support, providing care and education for abandoned children.

The creation of public spaces, such as squares and parks, also enhanced the quality of life for Florence’s residents. These areas became centers of social interaction and civic life, reflecting the Medici’s commitment to the welfare of the city.

Modernization and Unification

19th Century Developments

The 19th century was a period of profound change for Florence, marked by modernization efforts and significant political developments that culminated in the unification of Italy. The city’s transformation during this time reflected broader trends of industrialization and nationalism that swept across Europe.

Urban Renewal and Infrastructure

The modernization of Florence began in earnest in the early 19th century. As part of a broader movement to improve urban infrastructure, the city saw significant investments in public works. This included the expansion and paving of roads, the construction of bridges, and the enhancement of public buildings. The aim was to facilitate trade, improve sanitation, and accommodate a growing population.

One of the key projects was the construction of the Florence-Siena railway in 1849, which connected Florence to other major cities and fostered economic growth. The development of new transportation networks, including tramways and improved roadways, facilitated the movement of goods and people, further integrating Florence into the national and European economies.

Architectural and Cultural Revival

The 19th century also witnessed a revival in architecture and culture in Florence. Influenced by the Romantic movement, there was a renewed interest in the city’s medieval and Renaissance heritage. This period saw the restoration of several historic buildings, including the Palazzo Vecchio and the Bargello. Architects like Giuseppe Poggi played a crucial role in these restoration efforts, blending historical styles with modern needs.

Poggi’s most significant contribution was the transformation of Florence’s urban landscape. Appointed in 1864 to modernize the city, Poggi designed the viali, a series of wide boulevards encircling the historic center, inspired by the Parisian boulevards. His plan also included the creation of new parks and public spaces, such as the Parco delle Cascine and the Piazzale Michelangelo, which offered panoramic views of the city and became popular recreational areas.

Florence as Capital of Italy

Florence’s role in the unification of Italy was pivotal. The unification, known as the Risorgimento, was a complex process that sought to consolidate various independent states and territories into a single nation. Florence, with its rich cultural heritage and strategic location, played a significant part in this movement.

The Temporary Capital

In 1865, Florence became the capital of the newly unified Kingdom of Italy, succeeding Turin. This decision was made to placate the Tuscan population and to leverage Florence’s symbolic status as a center of Italian culture and history. The designation of Florence as the capital necessitated further modernization to accommodate the administrative needs of the new government.

The transfer of the capital brought a wave of political activity and intellectual fervor to the city. It also spurred economic growth, as new government buildings, residences, and infrastructure projects were undertaken to support the expanding bureaucratic apparatus. This period saw the construction of important buildings such as the new railway station, Stazione di Firenze Santa Maria Novella, which became a central hub in the Italian rail network.

However, Florence’s tenure as the capital was short-lived. In 1871, the capital was moved to Rome following its capture from the Papal States, which marked the final act of Italian unification. Despite this, the brief period as the capital left a lasting impact on Florence, accelerating its modernization and enhancing its national significance.

20th Century Developments

The 20th century brought both challenges and opportunities for Florence. The city faced the upheavals of two world wars, economic transformations, and social changes that reshaped its identity and infrastructure.

World Wars and Reconstruction

Florence, like much of Europe, was deeply affected by the World Wars. During World War I, the city experienced economic hardship and social upheaval, but it was World War II that had a more profound impact. Florence was occupied by German forces in 1943, and the city suffered significant damage during the Allied liberation in 1944. Historic bridges, including the Ponte Santa Trinita, were destroyed by retreating German troops, although the Ponte Vecchio was famously spared.

The post-war period saw extensive reconstruction efforts aimed at restoring Florence’s damaged infrastructure and historical sites. The rebuilding of the Ponte Santa Trinita, completed in 1958 using original stones retrieved from the Arno River, symbolized the city’s resilience and commitment to preserving its heritage. The Italian government and international organizations provided funding and expertise to support these restoration projects, ensuring that Florence’s cultural legacy was maintained.

Post-War Cultural Revival

After World War II, Florence experienced a cultural and economic revival. The city became a center for fashion, art, and tourism, attracting visitors from around the world. The restoration of historic sites and the preservation of Renaissance masterpieces reinforced Florence’s status as a global cultural capital.

The establishment of numerous cultural institutions, such as the Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, an annual arts festival founded in 1933, helped to promote Florence’s cultural heritage. The festival, which includes opera, concerts, and ballet, became one of the most prestigious in Europe, drawing renowned artists and performers to the city.

Economic and Social Transformations

The latter half of the 20th century and the early 21st century saw Florence navigate the challenges of modernization while preserving its historical identity. The city’s economy diversified, with tourism, fashion, and education becoming major sectors alongside traditional industries like textiles and craftsmanship.

Tourism Boom

Tourism emerged as a cornerstone of Florence’s economy, driven by the city’s rich artistic and architectural heritage. Millions of visitors flocked to see landmarks such as the Florence Cathedral, the Uffizi Gallery, and the Palazzo Pitti. The influx of tourists spurred the growth of the hospitality industry, leading to the establishment of numerous hotels, restaurants, and tour services.

To manage the impact of mass tourism on the city’s infrastructure and quality of life, local authorities implemented measures to promote sustainable tourism. This included regulating tourist flows, preserving historical sites, and enhancing public transportation.

Education and Research

Florence also established itself as a center of higher education and research. The University of Florence, founded in 1321, expanded its faculties and research programs, attracting students and scholars from around the globe. The city became a hub for academic conferences, cultural exchanges, and international collaborations, furthering its reputation as a center of intellectual excellence.

The European University Institute, established in 1972, added to Florence’s academic prestige. This institution, focused on postgraduate and doctoral studies in social sciences, law, and history, attracted a diverse international community of scholars and researchers.

Conclusion

The history of Florence is a testament to its enduring legacy as a center of art, culture, and innovation. From its ancient beginnings to its prominence during the Renaissance and beyond, Florence has left an indelible mark on the world. Its story is one of resilience, creativity, and timeless beauty.

F.A.Q.

Florence was founded by the Romans in 59 BC, originally named Florentia.

The Medici family, particularly through their patronage of the arts and support for intellectual pursuits, played a crucial role in fostering the Renaissance in Florence.

Some famous landmarks in Florence include the Florence Cathedral (Duomo), the Uffizi Gallery, the Ponte Vecchio, and the Palazzo Vecchio.

Florence contributed to the Renaissance through its support for artists, scholars, and thinkers, leading to significant advancements in art, science, and culture.

Today, Florence is known for its rich history, stunning architecture, and cultural significance, attracting millions of tourists annually.

Florence has preserved its historical sites through extensive restoration projects and efforts to maintain its cultural heritage.